It’s More than a Job, It’s Who I aM

It’s More than a Job, It’s Who I am: The Intertwined Nature of Farming and Identity

Growing up in rural southern Alberta, I was surrounded by all types of farms, ranging from small hobby farms to large-scale farms and ranches. Many of my friends were from these farms, and knew that they would someday take over the family farm.

It was interesting to see how involved they were with the farm, and how that affected their future plans. They didn’t do some of the things the non-farming kids did, such as travel abroad for the summer or move far away for school — there was work to do on the farm and they had a duty to help their family. These younger years are critical to learn alongside their parents or grandparents to know the ins-an-outs of the industry if they ever wanted to take over that farm someday.

It’s more than a job. It’s an identity.

From the other side, I watched their parents take pride in their identity as a farmer. Many of them were third or fourth-generation farmers, and their families had entrusted them to be productive farmers and carry on the family legacy. So what happens when these farmers have children? The same values, beliefs, and teachings they learned are passed on to their children. In this way, young farmers have been conditioned to fit their family's expectation of what makes a “good farmer” -- a tailored identity to fit a standard.

In school, we learned about a famous psychologist named Sigmund Freud who tried to understand why people behave the way they do. He said:

“We are what we are because we have been what we have been”.

At the time, this didn't really mean anything to me, but when I started thinking about it in relation to the people I knew back home, it made perfect sense.

My farmer friends had a "farmer" identity that reflected the work they did and the values that were passed on to them from their parents and grandparents.

But here's where the quote becomes messy:

If we are what we are because that's what we've been, can we ever become something different? In the context of farming, how does a person retire from something that has been such an integral part of their identity for so long?

But how do you retire from a life-long identity?

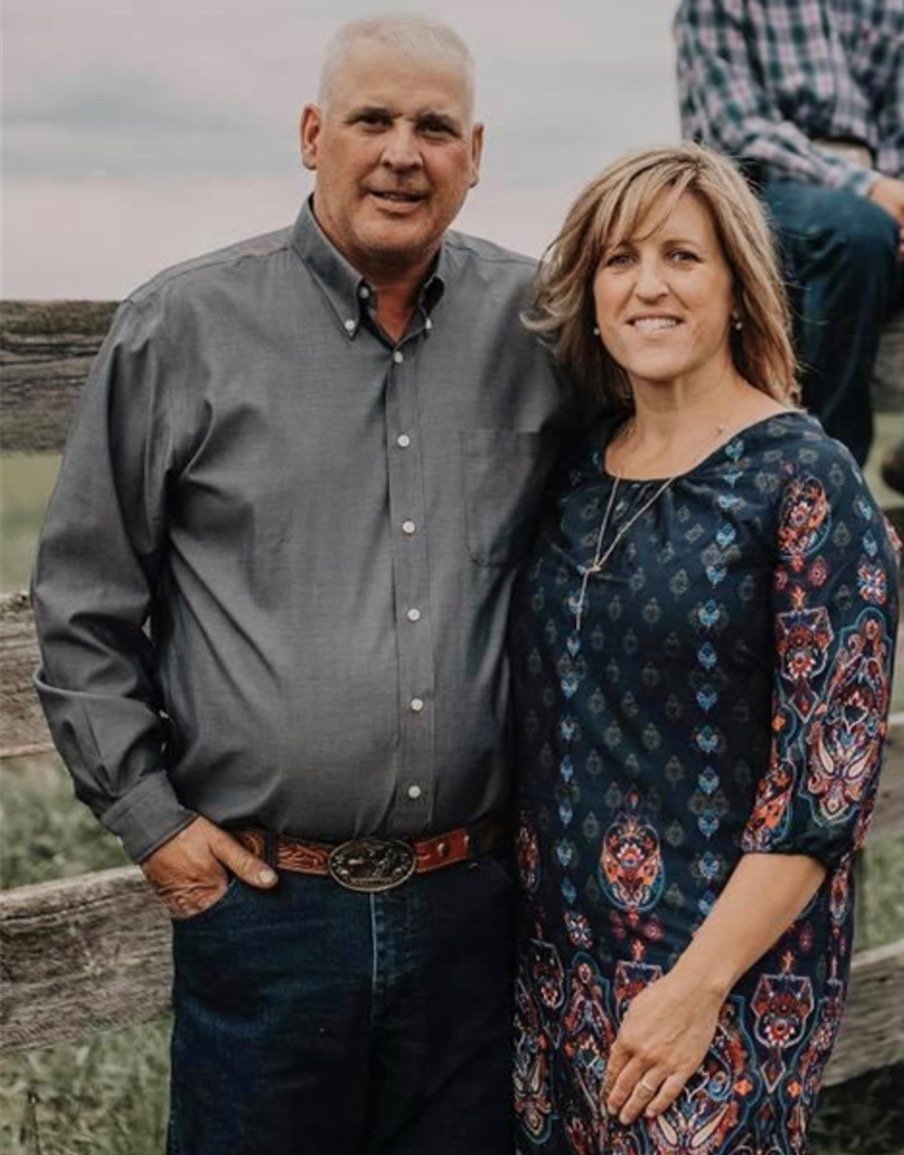

Pat & Tamara Newell

I decided to get someone’s perspective on this. Someone with insider knowledge about what it’s like to identify as a farmer your whole life but then be encouraged to think about retirement.

Pat Newell is a third-generation mixed farmer from Rockyford, Alberta. He farms 1,200 acres of wheat, barley, canola, and peas, and currently raises 100 pairs of cows and their calves. When he’s not running the farm, Pat is running his business trucking machinery, which he has done for 10 years.

Pat has been farming for nearly 40 years, and started when he was just 15. As Pat explained, he feels “very connected to the land, and the farm”, as they have been so strongly intertwined in his life from a young age. He says that living and working on his family farm “helped build my character and shape who I am today”.

During my interview with Pat, we discussed retirement and what that looks like for him.

When retirement is looming, it’s time to step back from the family business. How does this affect farmers who have grown up living and working on the farm? Turns out, it’s one of the most challenging things a farmer will do. In Pat’s words, "Retirement scares me truthfully. It makes me feel uneasy, because it represents the last of my physical input into the farm.”

Farming into their “golden years”

Pat’s not the only one feeling this way and maybe putting off retirement. Recent Canadian census data showed that the average age of a farm operator in Canada increased from nearly 50 years old in 2001 to 56 years old in 2021.

This isn’t only a Canadian issue. A recent study in Australia found that when the relationships of home, occupation, identity and place have been intertwined for generations, a farmer views retirement as an abrupt end to their purpose in life. This self-identity and their connection to place is the cornerstone of their contributions. Without it, some farmers feel they have nothing left to contribute, which can bring upon a fear of not being valued or needed.

Retirement can be a time of positive change

Retirement can also be a time of personal growth and positive change! This is certainly true for Pat as he says, “On the other hand, it is exciting for me to see all my years of teaching being carried on through hopefully my children.” Researchers in Australia found that maintaining strong social relationships in the family while gradually moving towards succession of the farm can alleviate some of the stressors around retirement. Like Pat, farmer’s want to see their children succeed and carry on the legacy they have built on the farm.

When is the right time to retire?

So is there a point in a farmer’s life when they know they should retire? For Pat, it’s partly connected to being physically capable to do the work. He said, “I think declining health is a huge point when a farmer recognizes they need to retire.” This is true for a lot of farmers.

Yet research shows that poor health and diminished capacity to get the work done isn’t necessarily a driver of retirement. It’s more complicated than that. It might be more about the farmer's identity. There’s a lot of pressure to live up to deeply entrenched ideals of the “good farmer”, you know, the one who works long hours, is stoic, strong, and independent. Research on dozens of farmers all tell the same story: It’s harder to uphold these expectations as you get older. But despite these challenges, many farmers will delay retirement. The boundaries for when to retire are blurred for farmers. As Pat says, “I feel retirement is hard… there is no set age which requires [a farmer] to make a decision that they can no longer do the job they have always known.”

When I asked Pat if farmers ever fully retire, he said “Some farmers are different, but I feel the real connected ones are committed to their last days. No, a true farmer never retires.” A recent study in Alberta reported that farmers’ identities are a combination of their occupational, social and personal lives. That is, farming isn’t a job, it’s a way of life.

How to support farmers’ transition into retirement

So, what can we do to help farmers prepare and be more comfortable with the idea of retirement? One tip is to support farmers to gradually increase their interest in non-farming activities. Having interests or hobbies outside of farming will help a farmer see that retirement isn’t an “end of life” but instead it’s an opportunity to begin a new life stage.

There are some great programs across Alberta that can help too. For example, the Men’s Shed program targets men in particular. It’s a place where men can gather, work on projects, apply their skills and knowledge, and make new friends. For many, this program gives men a sense of purpose and a way to connect with others outside of their inner circle. Find a local Men’s Shed program near you!

Activities that your shed might have include:

Drop-in – socialize with coffee/tea

Bikes and bike repair

Woodworking and metalworking

Auto and small engine repair

Cooking

Gardening

Mentoring and skill-sharing

Walking or hiking

Volunteering

Listening and/or playing music

Watching topic-specific videos followed by discussion

Computers/technology workshops

Home repair

Health-related discussions and guest speakers

Casey is working on the Farm Transitions Study with Dr. Rebecca Purc-Stephenson. The project involves a multi-case study analysis of producers who operate a multigenerational farm in Alberta. We’ll be interviewing them and at least two of their relatives or employees to learn more about the succession planning process such as what resources they want or have found useful, and what challenges they have encountered.